Marine Scientists Use Sonar to Tell NJ’s Revolutionary War History

August 21, 2018

Where the Garden State Parkway crosses over the Mullica River, lies an unseen story of the American Revolution concealed by murky water. On Oct. 6, 1778, the British burned as many as ten merchant ships that had been captured by privateers operating out of Port Republic, N.J. in the Battle of Chestnut Neck, the first amphibious attack by the British in South Jersey. Working under letters of Marque issued by the Continental Congress, Port Republic privateers were licensed to overtake British merchant schooners. “Go out, harass the British ships, confiscate what you can. We need these goods and materials for our war effort. Thousands of privateers helped supply the troops for the Revolution,” explained Stephen Nagiewicz, a Stockton graduate and an adjunct professor in the School of Natural Sciences and Mathematics.

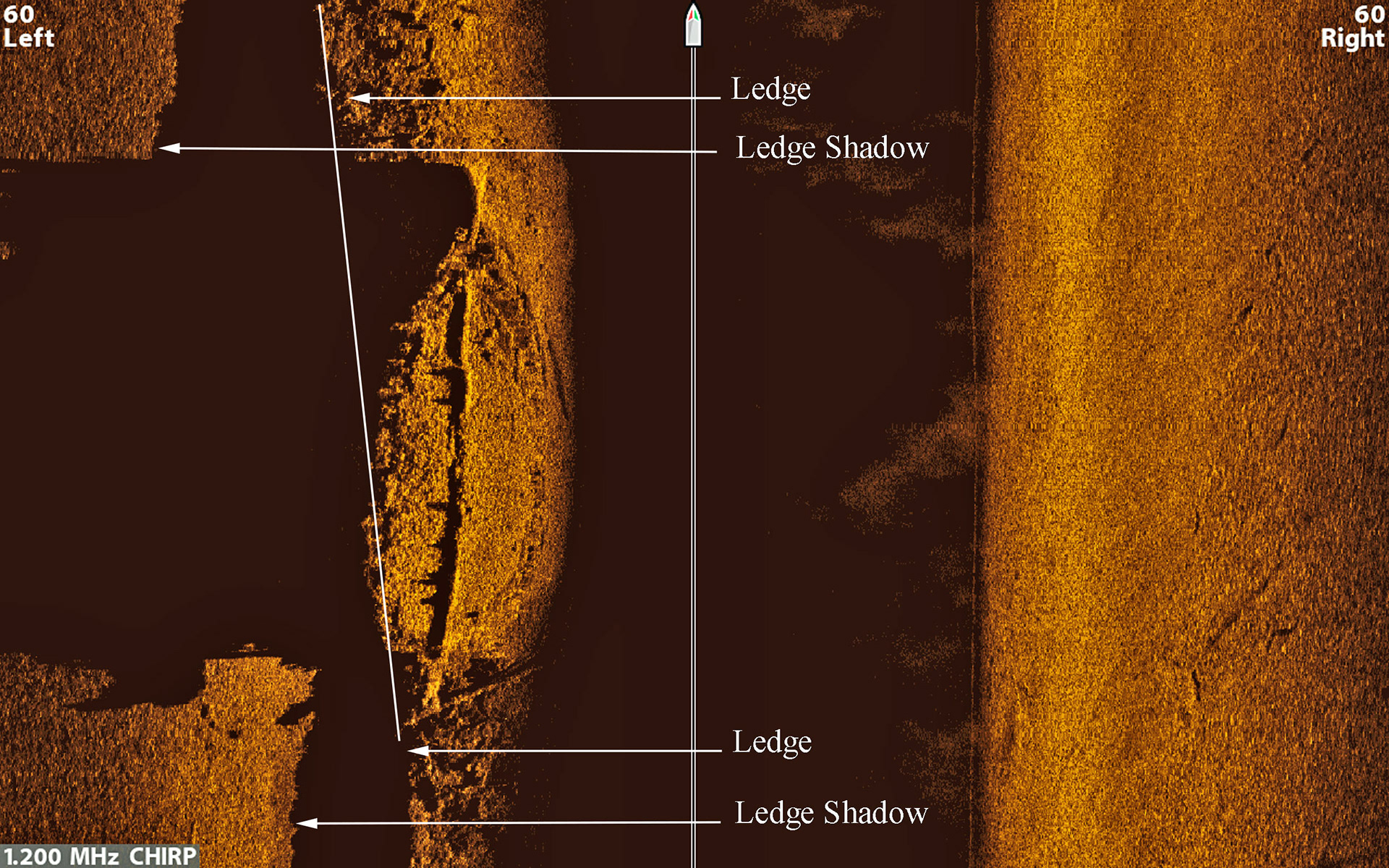

British ships captured by privateers were called prizes, and during the Battle of Chestnut Neck, the British salvaged any valuables and burned the prizes to leave the privateers at a disadvantage. A Stockton University research team, working out of the Marine Field Station, is using sonar to make acoustic images that will map four identified wrecks. The rest have yet to be found.

Using Science to See History

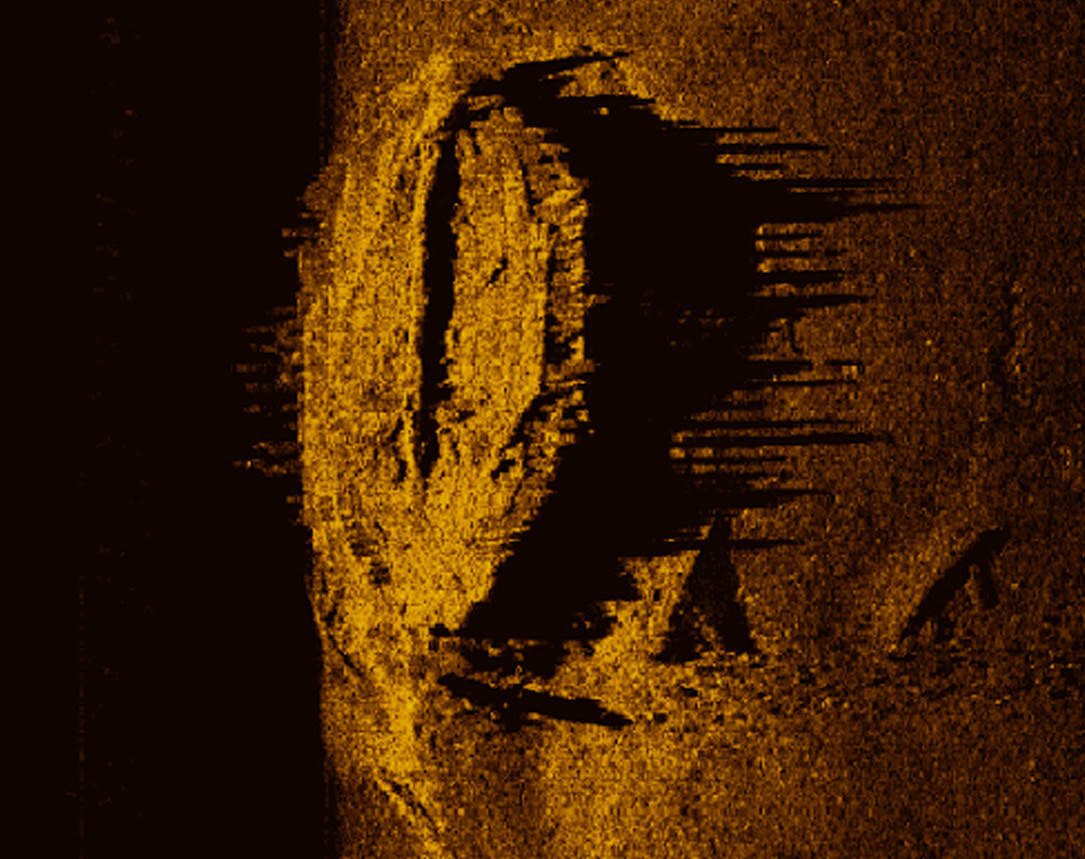

The schooners were burned to their waterlines and now rest on soft, mucky riverbed, slowly corroding in brackish water. They’ve been waiting patiently for 240 years to have their stories shared. Today’s work is a race against decay. Jaymes Swain, a senior Marine Science major with a concentration in Oceanography, points to the Bead Wreck on a computer screen in the cabin of the R/V Petrel, Stockton’s ocean-going research vessel. “In about 10-15 years, this will be gone,” he explains.

The Bead, named after the glass trading beads found at the wreck site, was nominated and placed on the National Register of Historic Shipwrecks by New Jersey divers in the mid-1980s. Colonists offered beads to Native Americans in exchange for items they needed to restart their lives in a new land. Stockton is revisiting the Bead wreck with modern technology to produce high resolution acoustic images documenting the historical remains before the wreck completely falls apart as it slides off the marsh slope. Stephen Nagiewicz teaches underwater archaeology courses and is working with his students to collect and process the data needed to re-build the wrecks in an everlasting electronic format accessible globally. Four to five hours of work translates to about 60 images. A complete acoustic image detailing a shipwreck requires hundreds of images. “We’ve been accumulating images of the wrecks for 18 months now. Each images adds new data. I probably have hundreds of images from all angles and still can use more,” said Nagiewicz.

August 21, 2018

Where the Garden State Parkway crosses over the Mullica River, lies an unseen story of the American Revolution concealed by murky water. On Oct. 6, 1778, the British burned as many as ten merchant ships that had been captured by privateers operating out of Port Republic, N.J. in the Battle of Chestnut Neck, the first amphibious attack by the British in South Jersey. Working under letters of Marque issued by the Continental Congress, Port Republic privateers were licensed to overtake British merchant schooners. “Go out, harass the British ships, confiscate what you can. We need these goods and materials for our war effort. Thousands of privateers helped supply the troops for the Revolution,” explained Stephen Nagiewicz, a Stockton graduate and an adjunct professor in the School of Natural Sciences and Mathematics.

British ships captured by privateers were called prizes, and during the Battle of Chestnut Neck, the British salvaged any valuables and burned the prizes to leave the privateers at a disadvantage. A Stockton University research team, working out of the Marine Field Station, is using sonar to make acoustic images that will map four identified wrecks. The rest have yet to be found.

Using Science to See History

The schooners were burned to their waterlines and now rest on soft, mucky riverbed, slowly corroding in brackish water. They’ve been waiting patiently for 240 years to have their stories shared. Today’s work is a race against decay. Jaymes Swain, a senior Marine Science major with a concentration in Oceanography, points to the Bead Wreck on a computer screen in the cabin of the R/V Petrel, Stockton’s ocean-going research vessel. “In about 10-15 years, this will be gone,” he explains.

The Bead, named after the glass trading beads found at the wreck site, was nominated and placed on the National Register of Historic Shipwrecks by New Jersey divers in the mid-1980s. Colonists offered beads to Native Americans in exchange for items they needed to restart their lives in a new land. Stockton is revisiting the Bead wreck with modern technology to produce high resolution acoustic images documenting the historical remains before the wreck completely falls apart as it slides off the marsh slope. Stephen Nagiewicz teaches underwater archaeology courses and is working with his students to collect and process the data needed to re-build the wrecks in an everlasting electronic format accessible globally. Four to five hours of work translates to about 60 images. A complete acoustic image detailing a shipwreck requires hundreds of images. “We’ve been accumulating images of the wrecks for 18 months now. Each images adds new data. I probably have hundreds of images from all angles and still can use more,” said Nagiewicz.

Acoustically Archiving Underwater Archaeology

Over time, the Bead has shifted in the current and is now situated on a slant that gives gravity the advantage in working against its preservation. Soon, the Bead will cease to exist. All that will remain are the acoustic images. The second of four wrecks, the Cramer, also found in the 1980s, has yet to be added to the national register and was recently mapped by Stockton as it falls within a State Historic District of the Battle of Chestnut Neck, a nationally registered event. Putting the Cramer on the map enables a protective State Historic District to be established for conservation and is the first step in nominating the wreck for listing on the National Parks Register of Historic Shipwrecks. Placing the wrecks on the register makes them “more available to the public and offers the opportunity to see and to learn about the history that happened here,” explained Nagiewicz. In addition to the Bead, there are two other shipwrecks off the coast of New Jersey on the Register, the Chauncey Jerome buried under the beach in Monmouth County, and the Robert J. Walker. Stockton partnered with recreational divers to assist the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) in mapping the Walker in 2014. The Walker was a U.S. Coast Survey steamer that sank just before the Civil War and was left mostly unexplored until Hurricane Sandy brought the need for surveying to the region, spurring new interest in a forgotten story.

Diving for Evidence

The third wreck, the Phoel, was discovered ten years ago by the late William Phoel, then an adjunct professor at Stockton and a fisheries scientist for NOAA, along with Peter Straub, now dean of the School of Natural Sciences and Mathematics, Steve Evert, director of Stockton’s Marine Field Station, and Vince Capone, a sonar consultant of Black Laser Learning. The wreck was named after Phoel who passed away unexpectedly on an expedition in the Amazon. Nagiewicz worked to designate the Phoel as an archaeological site by the state, and the next step is to nominate it, as well as the Cramer, for listing on the register. The Phoel’s wooden hull, oak frames and two mast steps are consistent with vessel design of the 18th century and are similar to the Bead and Walker, but to further prove its connection to the battle, Nagiewicz needed a closer inspection.

Over time, the Bead has shifted in the current and is now situated on a slant that gives gravity the advantage in working against its preservation. Soon, the Bead will cease to exist. All that will remain are the acoustic images. The second of four wrecks, the Cramer, also found in the 1980s, has yet to be added to the national register and was recently mapped by Stockton as it falls within a State Historic District of the Battle of Chestnut Neck, a nationally registered event. Putting the Cramer on the map enables a protective State Historic District to be established for conservation and is the first step in nominating the wreck for listing on the National Parks Register of Historic Shipwrecks. Placing the wrecks on the register makes them “more available to the public and offers the opportunity to see and to learn about the history that happened here,” explained Nagiewicz. In addition to the Bead, there are two other shipwrecks off the coast of New Jersey on the Register, the Chauncey Jerome buried under the beach in Monmouth County, and the Robert J. Walker. Stockton partnered with recreational divers to assist the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) in mapping the Walker in 2014. The Walker was a U.S. Coast Survey steamer that sank just before the Civil War and was left mostly unexplored until Hurricane Sandy brought the need for surveying to the region, spurring new interest in a forgotten story.

Diving for Evidence

The third wreck, the Phoel, was discovered ten years ago by the late William Phoel, then an adjunct professor at Stockton and a fisheries scientist for NOAA, along with Peter Straub, now dean of the School of Natural Sciences and Mathematics, Steve Evert, director of Stockton’s Marine Field Station, and Vince Capone, a sonar consultant of Black Laser Learning. The wreck was named after Phoel who passed away unexpectedly on an expedition in the Amazon. Nagiewicz worked to designate the Phoel as an archaeological site by the state, and the next step is to nominate it, as well as the Cramer, for listing on the register. The Phoel’s wooden hull, oak frames and two mast steps are consistent with vessel design of the 18th century and are similar to the Bead and Walker, but to further prove its connection to the battle, Nagiewicz needed a closer inspection.

Dives to the Phoel resulted in the recovery of artifact evidence.

A hand-struck brick tells that there was an onboard hearth for cooking. “If cooking onboard the ship was required, an area would typically be lined with ‘fire bricks’ to reduce the risk of fire on board. These fire bricks would continue to be used to protect galleys on wooden ships right up to the 18th century. As they do not decay in seawater, they are one of the more common finds on the wreck sites,” Nagiewicz explained. Charred wooden planks are proof that the ship was burned. Melted shards from glass bottles are additional proof. The pontil marks (scars left from the rod used to hold a hand-blown piece over the flames) can be analyzed to age the glass. Tree nails, or wooden pegs, predate iron nails and provide more evidence of an early technique in ship architecture. Although 16 feet is a shallow dive, the environmental conditions present challenges. In a Pinelands ecosystem, oak and pine leaves excrete tannins that stain the water black, so visibility is limited to about a foot. “It’s like diving in tea,” described Pete Straub, who dove to the Phoel with Nagiewicz and senior Marine Science major Jessica DiBlasi during a scientific diving Summer Intensive Research Experience (SIRE). “It’s difficult not to kick up fine sediment from the saltmarsh. Visibility goes down to inches when silt is stirred up,” he explained. Teredo worms, a mollusk whose appetite for wood earned them the nickname shipworms, have bored into the wreck, slowly eating away at history. In the ocean, coral and barnacles decoratively disguise wrecks hardening them into concrete, but in the brackish Mullica River, the wood remains visible for now. When Straub surfaced with a piece of charred plank, “it smelled like burnt wood, even 240 years later.” The wrecks fall within an estuary, where the river meets the sea, so the river current collides with the tides. The two dives were made at slack tide, eliminating any complication from the pull of the tides.

A hand-struck brick tells that there was an onboard hearth for cooking. “If cooking onboard the ship was required, an area would typically be lined with ‘fire bricks’ to reduce the risk of fire on board. These fire bricks would continue to be used to protect galleys on wooden ships right up to the 18th century. As they do not decay in seawater, they are one of the more common finds on the wreck sites,” Nagiewicz explained. Charred wooden planks are proof that the ship was burned. Melted shards from glass bottles are additional proof. The pontil marks (scars left from the rod used to hold a hand-blown piece over the flames) can be analyzed to age the glass. Tree nails, or wooden pegs, predate iron nails and provide more evidence of an early technique in ship architecture. Although 16 feet is a shallow dive, the environmental conditions present challenges. In a Pinelands ecosystem, oak and pine leaves excrete tannins that stain the water black, so visibility is limited to about a foot. “It’s like diving in tea,” described Pete Straub, who dove to the Phoel with Nagiewicz and senior Marine Science major Jessica DiBlasi during a scientific diving Summer Intensive Research Experience (SIRE). “It’s difficult not to kick up fine sediment from the saltmarsh. Visibility goes down to inches when silt is stirred up,” he explained. Teredo worms, a mollusk whose appetite for wood earned them the nickname shipworms, have bored into the wreck, slowly eating away at history. In the ocean, coral and barnacles decoratively disguise wrecks hardening them into concrete, but in the brackish Mullica River, the wood remains visible for now. When Straub surfaced with a piece of charred plank, “it smelled like burnt wood, even 240 years later.” The wrecks fall within an estuary, where the river meets the sea, so the river current collides with the tides. The two dives were made at slack tide, eliminating any complication from the pull of the tides.

Think Like a Sailboat: Project-based Education Gives Students a Head Start

The fourth wreck, not yet named, is the most recent discovery found and imaged by Nagiewicz and his underwater archeology students. “If I was a captain of a sailing ship 240 years ago or even today, it is exactly where I would have anchored,” Nagiewicz thought to himself when contemplating potential locations of the privateers’ prize ships. At that time in history, there was few piers, so ships would be anchored out in the river, Nagiewicz explained, so his floating classroom steered in that direction. While learning to deploy the sonar instrumentation and to process the imagery, Nagiewicz and his students saw the outline of the fourth wreck come into view on the computer screen. Now they are working to prove that it once belonged to a privateer. Steve Evert, director of the Field Station, is captain of the research vessel and helps students use the advanced scientific instrumentation on board. Evert’s crew is well-versed in operating the instruments and supports the learning process too. Stockton’s Remotely-operated vehicle (ROV) isn’t enough to image the wrecks that are obscured by murky water, but sonar’s sound waves travel through turbidity. When using sonar, “water clarity generally doesn’t matter,” explained Evert. “We’re never going to get a pretty picture—a literal digital picture of this wreck—because of visibility, but we can put together an acoustic picture using sonar,” he continued. “When we image something acoustically it’s not that much different than light in the sense that if it was dark out and I shined a flashlight you would see a shadow. We see the same thing acoustically, and that shadow often tells us more about the image than the actual reflectance of the target,” said Evert.

Undergraduate students become part of the crew and conduct the data collection, analyze the images and work alongside faculty experts in real-world science projects. Jessica DiBlasi, a U.S. Navy veteran, certified dive master and search and recovery diver, first used sonar in the military and is no stranger to diving in low light conditions. During public safety training, she wore blacked-out googles to simulate dangerous and dark conditions. Diving to the Phoel offered those same dark conditions after the three-foot mark. DiBlasi was stationed in Hawaii on the U.S.S. City of Corpus Christi where she served as a nuclear machinist mate and maintained nuclear and steam fluid systems on submarines. Working on the local wrecks has given her the chance to blend her interests in engineering and oceanography. While the boat navigated back and forth over the wrecks, we painted pictures onto a map with sonar, explained DiBlasi, who worked to map the Phoel wreck through an intensive research experience. She also captured footage of the wreck with an underwater camera. At the bottom, “it’s pitch black” everywhere the flashlight cannot reach. While searching for an anchor, DiBlasi spotted blue shards. She tucked them into the pouch of her dive vest and surfaced with pieces of the past that will be examined to date the wreck.

The fourth wreck, not yet named, is the most recent discovery found and imaged by Nagiewicz and his underwater archeology students. “If I was a captain of a sailing ship 240 years ago or even today, it is exactly where I would have anchored,” Nagiewicz thought to himself when contemplating potential locations of the privateers’ prize ships. At that time in history, there was few piers, so ships would be anchored out in the river, Nagiewicz explained, so his floating classroom steered in that direction. While learning to deploy the sonar instrumentation and to process the imagery, Nagiewicz and his students saw the outline of the fourth wreck come into view on the computer screen. Now they are working to prove that it once belonged to a privateer. Steve Evert, director of the Field Station, is captain of the research vessel and helps students use the advanced scientific instrumentation on board. Evert’s crew is well-versed in operating the instruments and supports the learning process too. Stockton’s Remotely-operated vehicle (ROV) isn’t enough to image the wrecks that are obscured by murky water, but sonar’s sound waves travel through turbidity. When using sonar, “water clarity generally doesn’t matter,” explained Evert. “We’re never going to get a pretty picture—a literal digital picture of this wreck—because of visibility, but we can put together an acoustic picture using sonar,” he continued. “When we image something acoustically it’s not that much different than light in the sense that if it was dark out and I shined a flashlight you would see a shadow. We see the same thing acoustically, and that shadow often tells us more about the image than the actual reflectance of the target,” said Evert.

Undergraduate students become part of the crew and conduct the data collection, analyze the images and work alongside faculty experts in real-world science projects. Jessica DiBlasi, a U.S. Navy veteran, certified dive master and search and recovery diver, first used sonar in the military and is no stranger to diving in low light conditions. During public safety training, she wore blacked-out googles to simulate dangerous and dark conditions. Diving to the Phoel offered those same dark conditions after the three-foot mark. DiBlasi was stationed in Hawaii on the U.S.S. City of Corpus Christi where she served as a nuclear machinist mate and maintained nuclear and steam fluid systems on submarines. Working on the local wrecks has given her the chance to blend her interests in engineering and oceanography. While the boat navigated back and forth over the wrecks, we painted pictures onto a map with sonar, explained DiBlasi, who worked to map the Phoel wreck through an intensive research experience. She also captured footage of the wreck with an underwater camera. At the bottom, “it’s pitch black” everywhere the flashlight cannot reach. While searching for an anchor, DiBlasi spotted blue shards. She tucked them into the pouch of her dive vest and surfaced with pieces of the past that will be examined to date the wreck.

Jaymes Swain is a student veteran who served in the Marines. He came to Stockton with a familiarity in boats and navigation, but now he’s acquiring a new skillset in operating scientific instruments.

Jason Sass, a sophomore Marine Science major with a concentration in Marine Biology, learned of the wrecks in Nagiewicz’ s lectures his freshman year. Intrigued by the stories, he needed to know more. He frequently stayed late after class to talk, and those after-class discussions led to an invitation to visit the wrecks. Sass enjoys freediving and spearfishing, but his study of the wrecks has left him wanting to spend more time under water. He is completing his certification in scuba diving this summer. “The history is what drove me and made me more interested in the wrecks. Who else gets this once in a lifetime opportunity,” he said. Sass’s research interest is in the Arctic, where he wants to explore how climate change affects the ecology of the food chain from plankton to whales.

Jason Sass, a sophomore Marine Science major with a concentration in Marine Biology, learned of the wrecks in Nagiewicz’ s lectures his freshman year. Intrigued by the stories, he needed to know more. He frequently stayed late after class to talk, and those after-class discussions led to an invitation to visit the wrecks. Sass enjoys freediving and spearfishing, but his study of the wrecks has left him wanting to spend more time under water. He is completing his certification in scuba diving this summer. “The history is what drove me and made me more interested in the wrecks. Who else gets this once in a lifetime opportunity,” he said. Sass’s research interest is in the Arctic, where he wants to explore how climate change affects the ecology of the food chain from plankton to whales.

Shannon Chiarel, a master’s student at Monmouth University studying Anthropology and Archaeology under Dr. Richard Veit, is focusing her dissertation on telling these ships’ stories. She is working with Nagiewicz and the Marine Field Station to collect data and evidence for the wrecks’ nomination to the register. Chiarel, who reads 18th century newspapers for clues, cannot depend on radio carbon dating to age the wrecks due to barnacles, algae and other environmental factors contaminating the samples. The wooden planks don’t have enough growth rings to accurately date the wood used in the construction. The answers she’s seeking live within the artifacts.

Anchors Aweigh

In an accidental encounter, a trawl caught a 250-pound wrought iron anchor belonging to the Bead. Stockton’s Marine Field Station was contacted to conserve the piece of history in coordination with the State Office of Historic Preservation. In 50 years, left unattended (out of water), the iron would rust to dust,” said Nagiewicz. Students will put the anchor through a chemical process called electrolysis to change the composition from iron to magnetite to slow rusting. The kedge-style anchor is another piece in the puzzle. “They were used in rivers that bend a lot,” Shannon Chiarel explained, to help the ship turn. “Imagine a 100-foot sailing ship with no engines using only sails. It couldn’t take sharp turns,” said Nagiewicz. The anchor would be taken out on a small boat and using a long line, the ship would pivot around the anchor. “On the Mullica, they probably had to do that every day,” said Nagiewicz.

In an accidental encounter, a trawl caught a 250-pound wrought iron anchor belonging to the Bead. Stockton’s Marine Field Station was contacted to conserve the piece of history in coordination with the State Office of Historic Preservation. In 50 years, left unattended (out of water), the iron would rust to dust,” said Nagiewicz. Students will put the anchor through a chemical process called electrolysis to change the composition from iron to magnetite to slow rusting. The kedge-style anchor is another piece in the puzzle. “They were used in rivers that bend a lot,” Shannon Chiarel explained, to help the ship turn. “Imagine a 100-foot sailing ship with no engines using only sails. It couldn’t take sharp turns,” said Nagiewicz. The anchor would be taken out on a small boat and using a long line, the ship would pivot around the anchor. “On the Mullica, they probably had to do that every day,” said Nagiewicz.

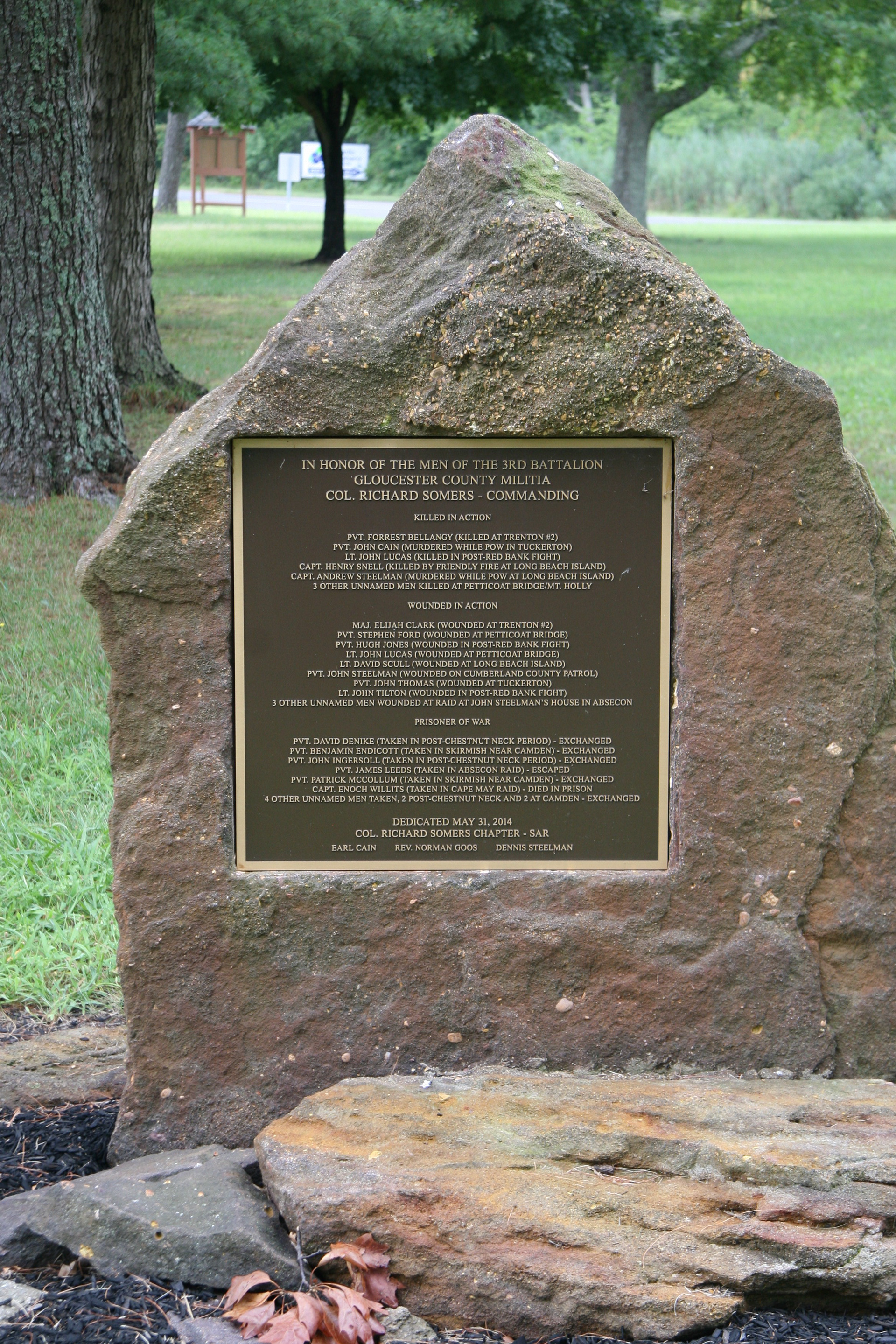

Honoring the Unsung Heroes

New Jersey served as a crossroads during the Revolution, and with the British occupying New York and Philadelphia, the privateers in Port Republic were in a position to make a stand. “Without these privateers there would likely not be a country for the work they did in harassing ships, capturing supplies and providing information,” said Nagiewicz. “We’re working to put more local history on the map, highlighting a little-known battle during the Revolutionary War only about five miles from Stockton's campus,” he added.

New Jersey served as a crossroads during the Revolution, and with the British occupying New York and Philadelphia, the privateers in Port Republic were in a position to make a stand. “Without these privateers there would likely not be a country for the work they did in harassing ships, capturing supplies and providing information,” said Nagiewicz. “We’re working to put more local history on the map, highlighting a little-known battle during the Revolutionary War only about five miles from Stockton's campus,” he added.

Stockton’s Marine Field Station equips students and faculty with the scientific instrumentation and mobility to do work that gives the public access to a piece of our country’s history. Gone are the days that these wrecks go unseen because a group of dedicated researchers are committed to honoring the unsung heroes and inviting the public to appreciate and remember their contributions.

Story and photos by __ Susan Allen This story was published on the Stockton News Page online in 2018